15 February, 2015

San Francisco

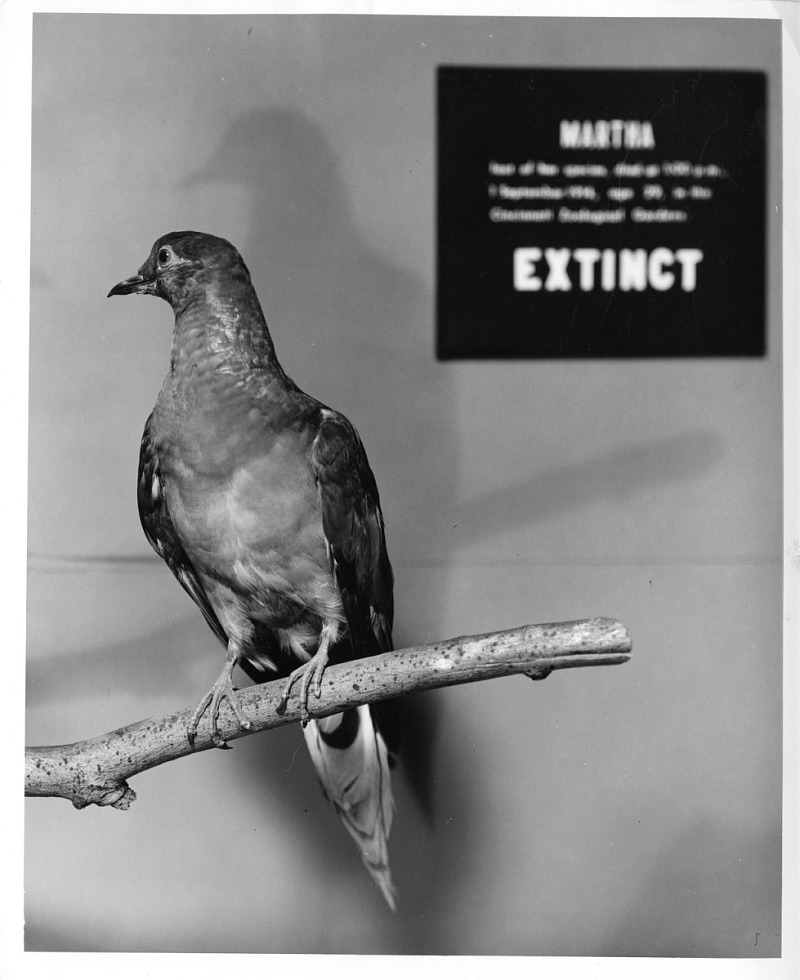

I was about 15 years old when I first saw a picture of Martha. It was a study in black-and-white, since color photography was uncommon back then. She was sitting all alone and forlorn - and for a very good reason.

There was nothing special about Martha; she was only a pigeon - one of billions of her kind that were so numerous that they once comprised some 40% of all North American birds!

Yet here sat this single, solitary specimen - the very last of her kind - languishing in a zoo in Cincinnati instead of flying free.

At 1:00pm, September 1, 1914, Martha died, and the Passenger Pigeon was officially extinct.

I read this in a book, given me by my grandparents. It was profusely illustrated with vivid color photographs showing birds of every species, color, and description in the course of nesting, feeding, flying and living. This was the case with all of the birds whose exquisite pictures were published in the book - all, that is, except this one, solitary, unfortunate little bird.

I understood the meaning of the word "EXTINCT" - I practically was on staff at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., having so frequently explored its lofty halls and fascinating exhibits as a young child. But the word only brought images of Wooly Mammoths, Sabre-Tooth tigers, dinosaurs and the like - not something so recent as fifty years ago!

I stopped reading and stared intensely at the bird's picture; the word "EXTINCT" now had such a final ring to it!

Mentioning this to my grandfather, he told me that "way back when" - before his time - these birds were so plentiful it sometimes took days for a single flock of them to pass a given point. They were so numerous they blotted out the sun.

They became over-abundant, the book further explained, and the mega flocks would descend upon farms and, like a noisy plague of locusts, wipe out whole crops. One farmer likened the noise of the birds to a fleet of scythes, slashing their way through crops.

Something had to be done. Like in locust plagues, farmers did what they could to protect their livelihood. They resorted to attacking the birds whenever and wherever they could. Pigeon kills were organized as normal farm activity whenever a flock was nesting in the area, much in the same way that rat-killing was carried out - and for the same reason.

Besides protecting their crops, it was to the farmers' best interest in another way: unlike their scrawny city cousins, these meaty passenger pigeons tasted good! The arrival of a flock may indeed mean some crop loss, but it also meant a time of good-eating. The birds became a delicacy.

Soon enough a whole industry developed around hunting these plentiful birds. Whereas only a few perished at the hands of enraged farmers or subsistence hunters, wholesale slaughter was wreaked by a professional industry. The telegraph allowed the location of a given flock to be transmitted over long distances, and railroads would quickly transport hunters to that location.

Like the buffalo which was also being hunted commercially during roughly this same time period, the massive flocks of passenger pigeons began to dwindle.

My great-great grandmother, Jenny Ellerd Moye of West Virginia, gave an eye-witness description of those pigeon hunts. The 27 Feb. 1955 edition of the Beckley (West Virginia) Post-Herald quotes Grandma Jennie:

"Best of all were the pigeon hunts!" Granma Jennie recalled.

"The men would all gather together along about dark," she says,"and with each provided with a club, a burlap sack (which they called a tow-sack), and a light, they would start out for a section commonly called the 'pigeon roost.'"

"While the women sat around and talked, the men would take their clubs and kill the pigeons."

"It wasn't a bit unusual to see one man come back with a tow-sack of pigeons he had caught himself.

The others all caught some, too. Sometimes the pigeons would all fly over in a group, and there would be so many that it just seemed like a black cloud. You can't imagine that now, can you?

But it was a common sight back then."

"When the men returned from their hunt, there was a huge wooden box in which the feathers were placed, and the pigeons were dressed like chickens, except that they were 'dry-picked'—that is, not scalded.

Both the men and women shared the work of dressing the pigeons, but upon completion of this work, the men were through with their work for the evening,so they peacefully sat back and talked and 'watched the young'uns' until the women cooked and served the delicacy"

"Everyone liked pigeons," Mrs. Moye says "and the feathers were used for pillows and pillow-licks"

The "pigeon-roost" she speaks about was located at Jumping Branch, WV.

Unlike the buffalo hunts that were taking place in the west, that saw bison killed mostly for pleasure, pigeons by and large were killed mostly for food.

What brought the passenger pigeon to extinction was not only the wholesale slaughter of the birds, but also the way they were killed.

Only adult birds were targeted, but since their nesting areas were the focus of the hunters' attacks, the nesting young died as well. This reduced the pigeon population drastically, and quickly, since there were very few individuals surviving to replace and to reproduce. By the time it was realized that the depopulation was so severe, it had reached the point of no return.

The bison, the passenger pigeon, and later other species would be driven to near extinction by unbridled hunting and overfishing. Add to that factory poisons, etc., and the outlook seems dismal if Mankind does not curb his greed and learn to be a better steward to this earth we live in.

As for the passenger pigeon, one might ask will we ever see great flocks of that beautiful bird grace our skies?

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

No comments:

Post a Comment